Synopsis

The French Annales School

World-Systems Analysis (WSA) emerged in the 1960-‘70s as a reaction to established scientific approaches. According to Wallerstein and other critics social sciences and humanities were too compartimentalized into distinct ‘sciences’ such as history, economic science, sociology, or political science. They also suffered from their respective flaws and shortcomings. History was too much concerned with specific stories in local historical contexts, with a strong focus on single facts and events, attributing a large degree of agency to political leaders and other persons – this is the so-called histoire évènementielle, which was opposed by historians such as Fernand Braudel (see below). They missed the wider picture that includes long-term trends, and the way systems and structures, which transcend the local and specific, determine the course of history and constrain the autonomy of actors.

In contrast, due to their positivist turn, post-WWII economists, sociologists, and political scientists were too much bent on emulating the natural scientists, with their search for scientific laws and the ambition to predict the future. Their parsimonious studies were to yield universal and a-historical laws. Yet, the latter overlooked historical context and ignored the reality that each historical period is building on the previous.

Finally, the study of non-Western peoples and regions by anthropologists, ‘orientalists’, etc. was criticized as being too Eurocentric, but also too describing and essentialist, as it was focusing on constant cultural characteristics of peoples, rather than considering dynamic evolution in the context of structural relationships within the wider world-system.

Wallerstein was strongly inspired by the French Annales school of historical thought, founded by Lucien Febvre and Marc Bloch in the 1920s, and by Fernand Braudel, who wrote after WW II, in particular. These scholars developed a holistic approach to history. This holism is present at three levels: 1) the integrated the sciences studying human society; 2) time; and 3) space. More precisely:

1) The need to integrate all the humanities (philosophy, history, law) and social sciences (sociology, economics, political science, etc.), as there is only one social reality. For this reason Wallerstein advocates unidisciplinarity, even rejecting multidisciplinarity or interdisciplinarity.

2) The acknowledgement that throughout history larger geographical areas go through distinguishable and different epochs. Such a longue durée or structural time represents an integrated historical system, based on relatively stable ordering principles.

3) The recognition that larger areas in the world constitute integrated geographical systems. Their localities are structurally interconnected through a division of labor, routes and sea lanes, trade and financial relations, typical economic practices, political power relationships, cultural elements, etc. (Wallerstein, 2007). In this fashion, Braudel regarded the 16th century Mediterranean region as an integrated ‘world-economy’ (Braudel, 1990).

Dependencia theory

When studying the decolonizing Global South, many social science practitioners adhered to the US-inspired ‘development’ approach, as laid out by State Department official Walt Rostow and others. They assumed that what the ‘developing countries’ needed to do in order to prosper, was to copy the Western countries trajectory in ‘stages of growth’, from feudal and rural towards democratic and advanced industrialized. Positivist research programs were believed to show the way. According to Wallerstein, such approach ignores that development in North and South occurs synchronically, and that structural conditions imposed by the North constrain – and often destroy – the possibilities of poorer regions and countries to catch up. In other words, the positivist development approach was leaving out structural dependencies between regions.

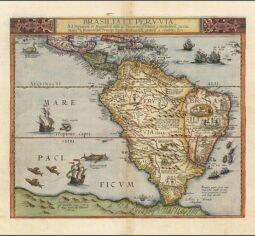

These criticisms paved the way for alternative approaches that would include world-systems analysis. One of the forerunners of WSA was the dependencia approach, which originated among southern economists. Some of them, like the Raúl Prebish, were also active in the UN Economic Commission for Latin America (ECLA). They theorized on the ‘unequal exchange’ between the ‘core’ (the North) and periphery (the South). Within this exploitative relationship the South exports raw materials and agricultural commodities to the North at unfair prices, while the North monopolizes the high value-added production and exports finished goods to the South. This process amounted to the ‘development of underdevelopment’ (cf. Andre Gunder Frank). This situation could only be solved through ‘de-linking’, breaking the dependency relationship. Alternative models, applied in Latin America and Asia, implied ‘import substitution industrialization’ (ISI), i.e. fostering an endogenous national industrial bases, which could grow and blossom under the protective shield of trade barriers such as import tariffs against industrial goods from the rich countries. Even though in real practice ISI had its drawbacks (corruption, inefficiencies), countries such as Brazil and India built there recent economic successes as emerging economies upon the industrial base they formed under ISI (Shannon, 1996; Wallerstein, 2007).

Basic assumptions and concepts

Based on these inspirations, the US scholar Immanuel Wallerstein (1930-2019) offers a systems theory for world politics based on holistic conceptions of space and time. In terms of space, structurally integrated regions (see above) in the world constitute a ‘world-system.’ The hyphen is important since it signifies that multiple systems have existed and that a system does not necessarily need to span the entire globe (saying ‘world system’ without hyphen would imply that there has only been one world-system). There are two types of world-systems: a ‘world-empire’ and a ‘world-economy.’ A world-empire is a world-system that is governed by one single political center or authority, even though it can encompass multiple cultures. An example is the Roman empire. A ‘world-economy’ is a world-system with multiple cultures that is governed by multiple political centers. During the ‘long 16th century’ (1450-1650) a capitalist world-economy originated in Western Europe and expanded to become truly global around 1900.

In terms of time, this capitalist world-system coincides with a structural time or longue durée between its inception and its end. As such, it constitutes a ‘historical system’ with a beginning and an end. Within the longue durée, Wallerstein recognizes economic cycles. For the phase of industrial capitalism (from the end of late 18th century on), he refers to the Kondratieff cycles (after the Russian Soviet economist Nikolai Kondratieff) of expansion and stagnation about 50-60 years. In addition, Wallerstein distinguishes cycles of rise and fall of hegemonic powers (see below).

The capitalist world-system

Capitalism needs a world-economy as it could not thrive in a world-empire. In a world-empire the state risks to become too powerful, so that the interests of the political rulers could override the main interest of the capitalists, namely endless capital accumulation. In a world-economy capitalists always have an exit option and can mobilize some states against others that threaten their interests. Due to financial-economic openness as well as technology and infrastructure making it easer to cross borders and bridge distances, there are currently even more possibilities to play off one state against another to put downward pressure on wages, taxes and regulation. At the same time, capitalists need states to protect their property rights, to support them against competitors, and receive other useful services.

The capitalist world-economy is characterized by a single, two-tiered division of labor consisting of core and peripheral production. Core production is the most knowledge-intensive, adds the most value, yields the highest profits and allows for high wages. In terms of ownership, it tends to be highly concentrated in the hands of quasi-monopolists or oligopolists. The latter instrumentalize the state for protection of their intellectual property rights, subsidies, targeted protectionism, etc. In other words, core producers need states that are tolerant towards oligopoly and excessive profits, since a genuinely free market – as envisioned by Adam Smith and other authentic liberals – would minimize profits. Peripheral production refers to standardized mass production with low value-added, low profits and low wages. There is no concentration but fierce competition between countless producers. In the long run, core-like products tend to become less knowledge-intensive and are downgraded to peripheral production. Importantly, lots of production in agriculture and mining is also peripheral.

Core production is carried out by a minority of the population, and most of it is located in the rich countries, the minority in the international states system. Most peripheral production is spread across the overwhelming majority of people and poorer countries. Hence, ‘core’ and ‘periphery’ refer to forms of production, and not regions, even though we can distinguish zones with predominantly core production (i.e. the high-income countries, incl. North America, Western Europe, Japan, Australia) and predominantly peripheral production (i.e. the low-income countries or least-developed countries, according to World Bank and UN terminology respectively, in Africa, Latin America, Asia and the Pacific). Note that all rich countries some peripheral production occurs, e.g. in illegal sweat shops. Some low-income countries might have some pockets of core production as well. As long as we are aware of these nuances, however, it is not too problematic to talk about ‘the core’ and ‘the periphery’ as zones with predominantly either one of the two kinds of production.

In addition, Wallerstein introduced the notion of semi-periphery, which actually denotes a geographical category, namely countries with a more or less equal distribution of core and peripheral production on their soils. This corresponds with the category of ‘emerging economies’, which includes Latin American countries like Argentina, Brazil and Mexico, some of the poorer ex-communist ‘transitional economies’ in Eastern Europe, South Africa, parts of the Middle East, India, China and South East Asian countries. For countries it is not easy to climb the ladder from periphery to semi-periphery, or from semi-periphery to core. Notable exceptions are the European states that could graduate from semi-periphery to core in the footsteps of Britain in the context of a growing industrial capitalism. A more recent example is Japan, which quite rapidly moved from periphery over semi-periphery to core through intensive state intervention from the 1868 Meiji Restauration onwards and massive US support post-1945 in the context of the Cold War.

World-systems analysis suggests a correlation between the place of countries in the capitalist world-economy and political regimes (even though this explanatory factor should be complimented with others given the complexity of the matter). Countries with mostly core production are usually governed by liberal democracies with ‘strong’ – in the sense of powerful and legitimate – governments. These countries’ wealth helps them to smooth redistribution and mitigate social struggles. The semi-periphery, in contrast, is more polarized between rich and poor. Governments are anxious to catch up with the rich countries (not to degrade to the periphery) and keep domestic tensions under control through repression. Therefore, governments in the semi-periphery have long been authoritarian, with a large sway over the economy and a big role for the military. Some semi-peripheral countries are run by fragile democratic regimes that can slide back into authoritarianism. Countries with mostly peripheral production tend to have unstable, weak and repressive (military) governments. Some of them are fragile and even failed states (Shannon, 1996; Wallerstein, 2007).

Hegemony

Similar to non-Marxist theorists such as George Modelski, Wallerstein recognizes the rise and fall of hegemonic powers as a cyclical phenomenon, albeit within what he conceives as the capitalist world-system. For Wallerstein, an ascending power first obtains the leading role with regard to agro-industrial production, then with regard to commerce, and finally with regard to finance. That power is hegemonic in the relatively short period that its leadership in these three dimensions coincides (Wallerstein, 1984).

This way, the modern world-state system has seen three hegemonies: the Dutch in the mid-17th century, the British in the mid-19th century and the US in the mid-20th century. The hegemonic powers are liberal states across the board. As rich countries, they can run a stable liberal regimes. As the strongest economy with lots of overseas interests, the hegemonic power has the most interest in an open world economy. The open markets they expect from foreign markets must often be reciprocated, while their own companies demand toll-free imports of foodstuffs for their workers and intermediate goods for their production. Capitalists usually prefer a hegemonic order for the stability and support the hegemonic power offers to business in the form of security services, credit, liquidity, providing a vast consumer market, and enforcement of liberal trading rules.

What causes the decline of a hegemonic power? A few mechanisms are at play. First, competing countries benefit from the open world economy. They can export to the hegemonic and other countries. They also emulate practices and technologies from the hegemonic power. While growing, some competitors become more powerful politically and economically. Second, as a liberal state, the hegemonic power needs to give in to strong pressures from below to raise wages, rendering the country less competitive. Third, in order to keep its leading position, the hegemonic powers faces increasing costs in the form of military commitments, more precisely policing the seas, maintain military bases across the world, and engage in local wars. In what the realist Paul Kennedy referred to as imperial overstretch (Kennedy, 1987), these costs become unbearable. All these problems are exacerbated during the second, downward phase of a Kondratieff cycle. By declining in relative terms, the hegemonic power loses political clout and legitimacy, and more and more recurs to violence, making its own problems worse. Ultimately a catastrophic ‘thirty years war’ sets in between blocs around the declining incumbent hegemonic power and a new candidate. From the ashes a new power begins its ascent to hegemony; this is not necessarily the main challenger, as in the real cases the latter was always defeated (see Table 2). Wallerstein considered the US as the hegemonic power for the entire international states system. Unlike Waltz, he did not consider the world order as bipolar, as he always regarded the Soviet Union as a secondary power participating to the world-system in the form of ‘state capitalism.’

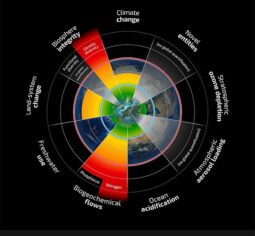

The end of the capitalist world-system and bifurcation

Wallerstein, who passed away in 2019, was convinced that we are both witnessing the end of US hegemony and the historic end of the capitalist world-economy. The student revolts of 1968, followed by the economic crisis of the 1970s and the US defeat in Vietnam reflected the second, downward phase of a Kondratieff cycle as well as US geopolitical decline. The 2003 war in Iraq showed the US aggressive because of weakness and uncertainty in light of the renewed geopolitical assertiveness of other power centers (Wallerstein, 2003). But capitalism as such is also in crisis. The fundamental problem is the crisis of profit: production costs are growing to such an extent that for products to remain sealable there is no margin for profit anymore. When wages become “too high”, industries relocate to lower-wage areas, but due to global labor scarcity the limits of this process are within sight. Upward pressure on wages becomes the new normal. Capitalism also faces the limits of depleting natural resources, polluting and global warming. In other words, ceaseless capital accumulation needs exploitation, but there is not much to exploit anymore. After 500 years the world is heading to an alternative to the capitalist world-system. Nobody knows what the future will bring; we stand at a ‘bifurcation.’ The future might be a non-capitalist, but grim, exploitative regime. Or it can go in the direction of a global democratic and ecologically sustainable world-system. Whereas Wallerstein’s world-systems analysis has a quite deterministic proclivity, the exceptional moment of bifurcation provides much room for activists devoted for either direction (KontextTV, 2015; Wallerstein, 2007). Present-day observers may doubt whether capitalism – which in response to past crises has often succeeded in reinventing itself – is really coming to end. But it is obvious that multiple crises are coming together that will require fundamental transformation after, and hopefully before, greater catastrophe.

Bibliography

Theories