Synopsis

A constant running through all administrations—and US foreign policy in general—is the ideological notion of US exceptionalism (Hughes, 2015; Patman & Southgate, 2016).

US exceptionalism refers to the idea that the United States, as a society and a state, is unique because of its foundational values. These values are centered on individual liberty, which implies democracy and a free-market economy. As such, these values are regarded as natural laws – pre-given, absolute, and non-negotiable. Consequently, they are considered superior to any other set of values. In the United States, a country with strong religious traditions, many even believe that these values come from God.

This belief has important implications for the US position in the world, particularly in light of the economic and military predominance the country has enjoyed since the First World War.

One implication is that the United States should not accept any authority above itself. This means it should never give up real sovereignty to a supranational body (for example, an EU-like global institution). Nor should it commit to multilateral organizations or agreements that fundamentally limit its sovereignty in matters related to national security or the essence of the ‘American way of life.’ This explains Washington’s attachment to the US veto right in the UN Security Council, the IMF, and the World Bank.

For the same reason, the United States is not a party to the International Criminal Court (ICC). In 2002, Congress even adopted the “American Service-Members’ Protection Act,” authorizing the President “to use all means necessary and appropriate to bring about the release of any [covered US or allied person] who is being detained or imprisoned by, on behalf of, or at the request of the International Criminal Court.”

US exceptionalism also explains, to a large extent, why the United States is the only country in the world that has not ratified the legally binding UN Convention on the Rights of the Child. There has consistently been a majority in Congress arguing that a global treaty should not interfere with how US children are raised and treated. In this case, not only US sovereignty but also parental sovereignty is perceived to be at stake. There is concern that the Convention may allow international oversight of matters such as (religious) education, social services and benefits, juvenile (penal) law, and reproductive rights. Discussions about the Convention and its potential impacts are not always rational or evidence-based.

In practice, US exceptionalism can manifest itself in various ways, depending on the position of the administration and/or Congress:

• US exceptionalism as a source of isolationism. Donald Trump’s America First program, for example, asserts that other countries or multilateral organizations should not dictate how American citizens live or how taxpayers’ money is spent. If the rules of the World Trade Organization no longer serve US interests, it is acceptable to disregard them. Moreover, US conservatives often view the UN and other multilateral institutions with contempt, describing them as ‘serving the interests of enemies’, ‘socialist’, ‘evil’, and a threat to everything the United States stands for, including its religious values.

• US exceptionalism and multilateral internationalism. The multilateralist internationalism of Presidents Woodrow Wilson and Franklin D. Roosevelt—and the more moderate versions of George H. W. Bush, Bill Clinton, Barack Obama, and Joe Biden—are also rooted in US exceptionalism. The combination of superior values and US predominance makes the country ‘bound to lead.’ As ‘the beacon of hope’, the United States sees itself as entitled to shape the multilateral governance structure or, at the very least, to occupy a privileged position in its decision-making. This explains why no president or Congress has ever contemplated giving up US veto powers in the UN and Bretton Woods institutions, or abandoning the highly controversial gentlemen’s agreement between the US and Europe that stipulates the head of the World Bank must be a US citizen and the head of the IMF a European.

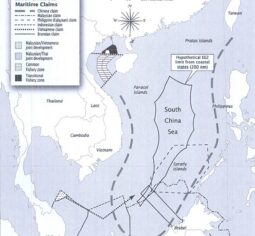

• US exceptionalism and unilateralism. US unilateralism can also be easily explained by the belief in exceptionalism. If the US government deems it necessary, it may intervene abroad regardless of international law or existing agreements. It claims the right to do so based on its “superior” values—and given its unmatched power, no one can effectively prevent it.

Bibliography

Topics

Theories