Synopsis

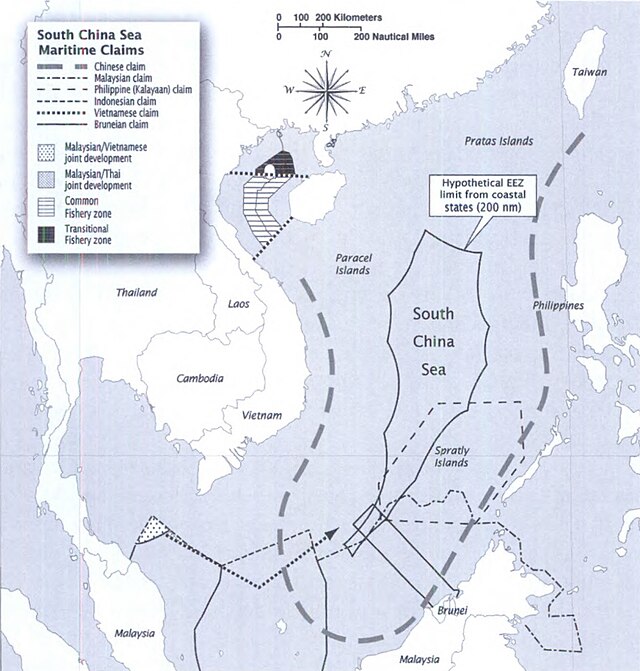

Etzioni defines spheres of influence (SOI) ‘[…] as international formations that contain one nation (the influencer) that commands superior power over others. For the formation to qualify as an SOI, the level of control the influencer has over the nations subject to its influence must be intermediary: lower than that of an occupying or colonizing nation, but higher than that of a coalition leader. Importantly, the means of control the influencer employs must be largely ideational and economic rather than coercive. Thus, it can be argued that, under the Monroe Doctrine, much of Central and South America was in the United States' SOI, and currently, North Korea is in Chinas SOI, while Japan is in that of the United States’ (Etzioni 2015).

In the Cold War context, Kaufman defined it as: ‘[…] a geographic region characterised by the high penetration of one superpower to the exclusion of other powers and particularly of the rival superpower’ (Kaufman 1976, 11). And Keal tells us that ‘[a] sphere of influence is a determined region within which a single external power exerts a predominant influence, which limits the independence or freedom of action of political entities within it’ (Keal 1983, 15).

Hast states that ‘[a] sphere of influence is not a permanent structure in the international system but is instead shaped and re-shaped in the interactions and discourses among human beings across state borders’ (Hast 2016). She takes this view following Wendt’s constructivist approach. She goes on to argue that a ‘[…] sphere of influence denotes not only a foreign policy tool but a complex of ideas on 1) international order and 2) acceptable and unacceptable influence. By “international order” I refer to the rules and institutions that govern the functioning of the society of states. By acceptable and unacceptable influence I refer to the sphere of influence as a normative concept, one embodying certain assumptions about right and wrong’ (Hast 2016).

Moreover, Hast avers that ‘[t]he concept is characterized by a conflict between the lack of theoretical interest in it in IR and, at the same time, the frequent use of it in political discourse. Sphere of influence is a contested concept that has awaited theoretical assessment from a historical perspective for too long. The problem with spheres of influence is that there is no debate on the meaning of the concept. It simply is in its simultaneous vagueness and familiarity' (Hast 2016).

Another issue with this concept is that historically it has focused on great powers, as put by Ferguson and Hast: ‘[s]maller states are seen as little more than pawns in the great powers’ geostrategic games. As a corrective to this view, this issue recognises that every political actor involved in a project of spheres of influence has their own agency, their own agenda, their own choices to make. [They use a quote by Obama to highlight this:] “The days of empire and spheres of influence are over. Bigger nations must not be allowed to bully the small, or impose their will at the barrel of a gun (Obama 2014)” ‘ (Ferguson and Hast 2018). This is a different world view to the one post-cold war, when as Etzioni points out: ‘[t]he strong still imposed their will on the weak; the rest of the world was compelled to play largely by American rules, or else face a steep price, from crippling sanctions to outright regime change’ (Etzioni 2015). Graham Allison points out that post-cold war ‘[s]pheres of influence hadn't gone away; they had been collapsed into one, by the overwhelming fact of U.S. hegemony’ (Allison 2020). This however, might not be the case at present as great powers and other states struggle to form their own SOI.

Moreover, Hast tells us that there seems to be little interest in IR from a theoretical view: ‘[o]ne explanation for the lack of interest in conceptualizing spheres of influence is that there are already plenty of other concepts describing international influence’ (Hast 2016). These other concepts she mentions are regional security complex, empire lite, regionalism and soft power.

Etzioni conjectures that SOI have somehow been intricate into keeping the international order, and takes both a realist and liberal point of view to reach this conclusion. ‘[…] zones of influence achieved largely through ideational and economic means contribute to the international order because they reduce the risk of war. A realist is hence likely to hold that they should be opposed only if they violate the core interests of the nation that tolerates the development of such a sphere by another nation. […] Moreover, from a liberal viewpoint, SOI need not conflict with the rule-based international order, because their norms ban only coercive interference by one nation in the internal affairs of others, not influence by non-lethal or traditional soft power tactics such as media broadcasts, student exchanges, and trade, among others. Finally, SOI seem to have a major constructive role to play in helping a prevailing global superpower, such as the United States, adapt to a rising regional power, such as China’ (Etzioni 2015).

Bibliography

Topics

Theories

About Course

pruba</….p>

What to learn?

Instructor