Synopsis

An ideal-type of an international regime covering a specific issue consists of one single formal intergovernmental organization (FIGO) overseeing the implementation of a single treaty. This is about how the founders of the UN in 1945 imagined multilateral cooperation. When national governments cannot do it alone, they are complemented by a UN specialized agency such as the WHO, Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), or the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) for assisting national policies and for global norm setting.

Defining international regimes complexes

However, in the real world of the 21st century, we see how most issue areas are simultaneously governed by a plethora of formal and informal IGOs, treaties and informal agreements, public-private partnerships, international private organizations, etc. Within these global governance architectures, the UN with its agencies has just become one actor among many. These architectures are referred to as regime complexes (Alter & Raustiala, 2018). Raustiala and Victor initiated research on this phenomenon by defining a regime complex as “an array of partially overlapping and non-hierarchical institutions governing a particular issue-area” (Raustiala & Victor, 2004). Keohane and Victor interestingly define a regime complex as situated in the middle on the continuum between “comprehensive international regulatory institutions, which are usually focused on a single integrated legal instrument” and “highly fragmented arrangements” (Keohane & Victor, 2011).

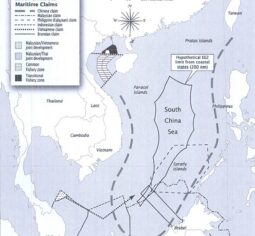

The delineation of a regime complex (where it begins and where it ends) is seldom clear-cut. Take for example the energy regime complex, which not only consists of energy institutions in the narrow sense – incl. the International Energy Agency (IEA), the Organization of Oil Exporting Countries (OPEC) – but also organizations with a say on energy such as the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), G20 or FAO (when it comes to biofuels). Furthermore, all regime complexes – take for example energy and climate – obviously have overlaps and intersections with others.

Moreover, one can conceive one regime complex – for example energy –, but on closer inspection, one discovers sub-complexes underneath. Thus, the general energy regime complex comprises the more specific regime complexes of oil, coal and gas; the regime complexes of collaboration on energy efficiency and renewable energy; the nuclear energy regime complex; etc.

The latter in turn falls apart into three ‘lower’ regime complexes: nuclear safeguards (i.e. against the proliferation of nuclear weapons); nuclear collaboration and safety (i.e. on technology and safety of civilian applications); nuclear security (i.e. policies against terrorism with nuclear material). Each of these regime complexes includes a host of formal and informal institutions and arrangements. In other words, this hierarchical landscape of international cooperation more and more resembles the universe with its planets, solar systems, galaxies and inter-galactic clusters...

The evolution of regime complexes

The phenomenon of regimes complexes has sparked a lot of interesting questions. One set revolves around the driving forces of the evolution of regime complexes. One way of tracing and explaining the evolution is considering the interplay between functional (i.e. developments on the ground that induce responses from the international community), strategic (i.e. inter-state interactions based on interests and power), and organizational logics (incl. the autonomy of secretariats of international organizations and path dependencies following from the existing institutional reality) (see e.g.Van de Graaf, 2013).

Consider the way the G20 summit took the lead in the regime complex for financial stability from 2008 onwards. This promotion of the G20 was clearly induced by the global financial crisis (functional logic). Major powers preferred an informal setting to retain maximal political control without binding commitment (strategic logic). The elevation of the existing, low-profile and slumbering G20 of finance ministers and central bankers which already existed since 1999 to a leaders’ summit had much to do with path dependency: in the midst of the crisis, leaders wanted to avoid lengthy discussions on the right composition of the group. In addition, the informal and relatively concise major power grouping represented by heads of state and government allowed for flexible and powerful crisis management (organizational logic) (see e.g.Viola, 2015; Viola, 2019).

The effects of regime complexes

The rapid expansion and deepening of regime complexes raises many questions on their effects. A policy-relevant question is whether regimes complexes and their intricate interrelationships are a good or bad thing for international cooperation. There is no black-and-white answer to this question.

Some have argued that regime complexity has the advantage of adding flexibility and adaptability to international cooperation as an alternative to putting all one’s eggs in one basket, i.e. one big comprehensive multilateral bureaucracy. It might be good to split a governance architecture for an issue area into more specialized institutions, after which a sensible division of labor gets settled; to allow for ‘healthy’ competition against institutions; to let some states create a new institution because they are unhappy about the incumbent ones (e.g. BRICS creating the New Development Bank to complement the Western-dominated World Bank and regional development banks).

Others find the increasingly fragmented nature of global governance problematic. For them, the erosion of UN centrality made way for a governance chaos full of inefficiencies such as duplication of work; dysfunctional ‘turf wars’ between institutions; normative frictions between parts of the regime complex (e.g. vaccines as global public good or as intellectual property?); powerful states’ tactics of ‘forum shopping’ (i.e. moving a discussion to another forum with a more ‘favorable’ composition or norms) and ‘regime shifting’ (i.e. moving an entire issue area from one institution to another); gaps left; and lack of central oversight and accountability (Gehring & Faude, 2013).

Daniel Drezner contends that regime complexes can even reinforce power inequalities between states in two ways:

1) Smaller and poorer countries lack the resources for expertise, diplomatic capability and travel to join and follow-up on all the meetings and processes that a regime complex entails. Hence, the great powers regain the advantage in negotiations.

2) Regime complexes tend to undermine official treaty-based multilateralism, of which it is known that it somewhat binds great powers and empowers the weaker.

Thus, paradoxically, regime complexity as the summum of international cooperation brings us ontologically back to the Hobbesian anarchy described by realists (Drezner, 2009).

Anyway, the management of regime complexes poses a formidable policy challenge and a new avenue for research. Ontologically, recent years have witnessed a trend towards regaining control over the chaos out of a need for oversight and strategic steering. The lead role of the G20 with regard to financial stability and the joint lead of the G20 and OECD on international tax collaboration are illustrations of this (Viola, 2015). By launching the comprehensive 2030 Agenda and Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in 2015 and putting the new High-Level Political Forum for Sustainable Development in place to oversee the implementation, the UN made a bid to leadership over the multidimensional policy domain of sustainable development, which addresses social, economic and ecological challenges in an integrated way (Bernstein, 2017).

Bibliography

Topics

Theories