Synopsis

Pivot states – referred to in some literature as ‘pivotal states’ – are countries that play strategically significant roles in the contemporary international system, despite not being great powers. The phenomenon itself is not new, but in an increasingly multipolar world without clear leadership and without the disciplining bipolarity of the Cold War, a number of middle powers have gained strategic importance and leverage due to their population size, economic assets, military capabilities, and/or geographical position.

Ian Bremmer defines a pivot state as “a country able to build profitable relationships with multiple other countries without becoming overly reliant on any one of them.” In his book on the ‘G-zero world’, he continues: “In a world with regional centers of gravity, one in which no country plays the global leader, governments must create more of their own opportunities. The ability to pivot is a critical advantage.” He mentions Brazil and Turkey, among others, as good examples (Bremmer, 2012).

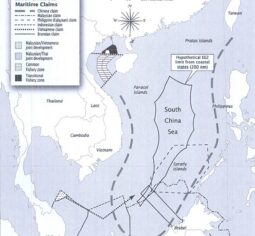

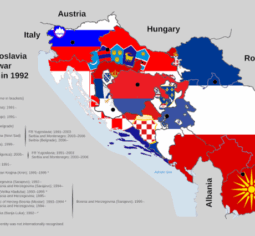

According to Sweijs et al., “[p]ivot states are states that possess military, economic or ideational strategic assets that are coveted by great powers. Pivot states are caught in the middle of overlapping spheres of influence of multiple great powers as measured by associations that consist of ties that bind (military and economic agreements and cultural affinities) and relationships that flow (arms and commodities trade and discourse). A change in a pivot state’s association has important repercussions for regional and global security. States that find themselves in overlapping spheres of interest are focal points of where great power interests can collide and also clash. States located at the seams of the international system have at various moments in history been crucial to the security and stability of the international system” (2014).

According to Bart Gaens, “[I]ndia is increasingly turning into a pivotal state, in the sense both of “being a pivot” and of actively “pivoting”. India is becoming “a critical point around which great powers’ actions revolve” (i.e. a pivot). For example, the West is aware that strategies to balance China, including the United States’ and Japan’s free and open Indo-Pacific (FOIP), are impossible to implement without the support of India, and also need India as a potential economic alternative to China. At the same time, India is also a state that shapes the regional and global security environment through its policy choices (i.e. pivoting). India’s unwillingness to criticise Russia’s actions in Ukraine is an example. Rather, New Delhi has boosted trade ties with Russia, continues to buy cheap oil from Moscow, and remains dependent on the country for arms supplies. In short, multi-alignment is a key strategic foreign-policy tool for India as a pivot state, which has further repercussions on the global security environment” (Gaens, 2026).

Another example of a pivot state is Kazakhstan, which since independence opted for a ‘multi-vector diplomacy’ – which means developing good relations with Russia, China, the US, EU and others alike (Neafie, 2023; Roberts & Ziemer, 2024).

As great powers compete, maintaining strong relations with the pivot states – or preventing them from aligning too much with rival powers – becomes critical. In this environment, pivot states exercise agency through strategic autonomy, using the attention and rivalry among great powers to further their own interests. This behavior is closely related to the concept of ‘hedging’, which carries the additional connotation of seeking insurance against a potential deterioration in relations with any particular great power.

Bibliography

Topics

Theories