Synopsis

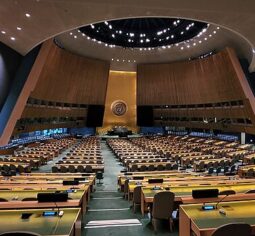

Orchestration refers to a specific mode of governance in global governance. Abbott et al. use the term to describe how intergovernmental institutions (IGOs) sometimes use intermediary actors to govern a target actor: “In IGO orchestration, an IGO enlists and supports intermediary actors to address target actors in pursuit of IGO governance goals. The key to orchestration is that the IGO brings third parties into the governance arrangement to act as intermediaries between itself and the targets, rather than trying to govern the targets directly. More generally, one actor (or set of actors), the orchestrator, works through a second actor (or set of actors), the intermediary, to govern a third actor (or set of actors), the target” (Abbott, Genschel, Snidal, & Zangl, 2015, p. 4).

The authors do not conceive orchestration as a direct hierarchical line between the orchestrator and the intermediary: “Rather, the orchestrator uses ideational and/or material inducements to create, integrate and maintain a multi-actor system of soft and indirect governance, geared toward shared goals that neither orchestrator nor intermediaries could achieve on their own” (Abbott et al., 2015, p. 4).

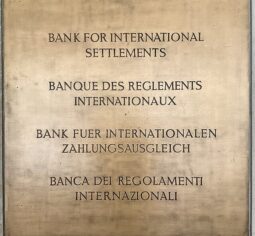

A clear example of orchestration can be observed in the way the G20, as an informal grouping of major powers, tasks formal intergovernmental organizations (FIGOs) such as the IMF, World Bank, or OECD with the design of policies on issues including financial stability, development, and taxation for subsequent implementation by their member states (Downie, 2022). Although the G20 as an institution exercises no direct authority over these FIGOs, the latter are generally willing to act on its behalf. This willingness stems not only from the fact that cooperation with a powerful forum like the G20 enhances the prestige and visibility of a FIGO’s secretariat, but also because G20 members politically dominate most of these organizations.

The case of the G20 is particularly interesting, as this group wields enough influence to play an orchestrating role across entire regime complexes. This became evident in the aftermath of the 2008 Global Financial Crisis, when the G20 tasked—and often funded—institutions such as the IMF, multilateral development banks, and the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision to take action within their respective domains to combat the crisis and strengthen national financial systems for the future. The G20 was also instrumental in expanding the membership of the Financial Stability Forum to include all G20 members and in transforming it into the Financial Stability Board. Hence, the G20 played an orchestrating role at the apex of the regime complex for global financial stability (Viola, 2015).

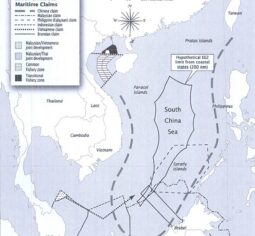

Within the regime complex of international tax cooperation, the G20 exercised an orchestrating role by providing the political steering necessary for the OECD to design and implement the new global regimes for a) automatic exchange of information with regard to individual tax payers’ accounts and b) the base erosion and profit shifting (BEPS) initiative to enhance the effective taxation of multinational companies, including a minimum tax (Kuhn, Cadzow, Heitmüller, Hearson, & Randriamanalina, 2024). By the same token, the G20 gave political impulses to the OECD, IMF and multilateral development banks with regard to tax capacity building in lower-income countries for domestic resource mobilization (Lesage & Lips, 2022).

Bibliography

Topics

Theories