Synopsis

The new wars concept was coined by Mary Kaldor. She argues the new in new wars has to do with globalisation and technology. “The new wars have to be understood in the context of the process known as globalization. By globalization, I mean the intensification of global interconnectedness – political, economic, military and cultural – and the changing character of political authority” (Kaldor 2012). Yet, this drive to interpret the changing nature of war is not new. For example, historian Martin Van Creveld one of the first to aver that war had experienced a transformation due, mainly, to two factors: nuclear weapons and the spread of low intensity conflicts (a term coined by the US army) (Creveld 1991).

Yet, it was Kaldor that expanded the study of ‘new’ in new wars and she describes new wars within the changes mentioned above. “First of all, the increase in the destructiveness and accuracy of all forms of military technology has made symmetrical war – war between similarly armed opponents – increasingly destructive and therefore difficult to win. The first Gulf war between Iraq and Iran was perhaps the most recent example of symmetrical war – a war, much like the First World War, that lasted for years and killed millions of young men, for almost no political result. Hence, tactics in the new wars necessarily have to deal with this reality.

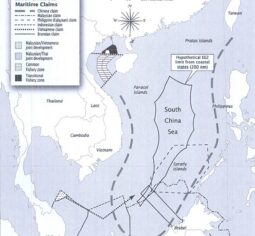

Secondly, new forms of communications (information technology, television and radio, cheap air travel) have had a range of implications. Even though most contemporary conflicts are very local, global connections are much more extensive, including criminal networks, diaspora links, as well as the presence of international agencies, NGOs, and journalists. The ability to mobilise around both exclusivist causes and human rights causes has been speeded up by new communications. Communications are also increasingly a tool of war, making it easier, for example, to spread fear and panic than in earlier periods – hence, spectacular acts of terrorism […] Thirdly, even though it may be the case that, as globalisation theorists argue, globalisation has not led to the demise of the state but rather its transformation, it is important to delineate the different ways in which states are changing. Perhaps the most important aspect of state transformation is the changing role of the state in relation to organised violence. On the one hand, the monopoly of violence is eroded from above, as some states are increasingly embedded in a set of international rules and institutions. On the other hand, the monopoly of violence is eroded from below as other states become weaker under the impact of globalisation. There is, it can be argued, a big difference between the sort of privatised wars that characterised the pre-modern period and the ‘new wars’ which come after the modern period and are about disintegration.” (Kaldor 2013).

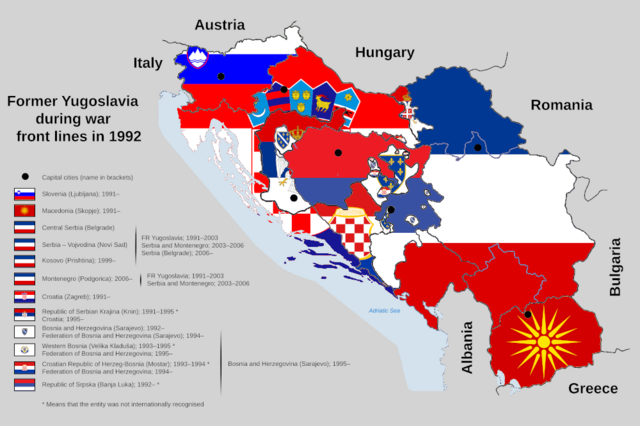

Kaldor further deepens into the concept: “These are wars that take place in the context of the disintegration of states (typically authoritarian states under the impact of globalisation). These are wars fought by networks of state and non-state actors, often without uniforms, sometimes they have distinctive signs, like crosses or RayBan sunglasses as in the case of the Croatian militia in Bosnia Herzegovina. They are wars where battles are rare and where most violence is directed against civilians as a consequence of counter-insurgency tactics or ethnic cleansing. They are wars where taxation is falling and war finance consists of loot and pillage, illegal trading and other war-generated revenue. They are wars where the distinctions between combatant and non-combatant, legitimate violence and criminality are all breaking down. These are wars which exacerbate the disintegration of the state – declines in GDP, loss of tax revenue, loss of legitimacy, etc. Above all, they construct new sectarian identities (religious, ethnic or tribal) that undermine the sense of a shared political community. Indeed, this could be considered the purpose of these wars. They recreate the sense of political community along new divisive lines through the manufacture of fear and hate. They establish new friend-enemy distinctions” (Kaldor 2005).

Various academics have criticised the concept of new wars, often commenting that these new wars are not new; as many of the factors described by Kaldor were present in wars throughout time. Others state that the term new war is too vague and too difficult to link to conflict theory (Chojnacki, 2006), and Henderson and Singer state that although helpful the concept tries to incorporate all types of war into one single concept, instead of focusing in their individual nature (Henderson and Singer, 2002). Perhaps the most extended criticism comes from Duffield, who does not dispute that war changes but he argues these ideas of ‘new’ in wars have to do with the Liberal interpretation of war. He argues, “What is under discussion now is not the issue of change per se, but how liberal peace has chosen to interpret the nature of this transition. War has been appropriated in such a way as both to reproblematise security in terms of underdevelopment becoming dangerous and, through its radicalisation, to reinvent the role of development as well” (Duffield 2001).

Bibliography

Topics