Synopsis

A liberal-inspired reaction against the realist pessimism and almost exclusively power-based view on international cooperation was mounted from the end of the 1970s. Neoliberal institutionalism emerged as the most influential liberal strands to explain durable international cooperation. The prefix ‘neo-’ refers to the way this contemporary approach ties in with classical liberalism’s optimism, appreciation of interdependence and belief in international cooperation (cf. Wilson, Kant). But this time, neoliberal institutionalism also signs up to the post-Second Word War positivist and behavioralist tradition to tackle the question more scientifically. As an institutionalist approach, this theory argues that international institutions matter: the mere fact that they exist, often makes a difference in international politics. In other words, international institutions mediate between the power- and interests-based politics of states and actual outcomes.

Complex interdependence and the demand for international cooperation

Neoliberal institutionalists start their argumentation with the same assumptions as the neo- or structural realists: the international system is anarchical; states are rational utility maximizers (i.e. rational egoists); they pursue their own (security) interests. But from there, ways part.

Neorealists build on these assumptions to explain and predict conflict of interests, relative gain-thinking (i.e. the obsession with the other winning more from cooperation, as an obstacle to cooperation), free riding and cheating. From there, they draw the gloomy conclusion that long-lasting and deep international cooperation on anything important is unlikely.

In contrast, neoliberal institutionalists add the very important observation that the anarchical international system has undergone an ontological transformation in the course of the 20th century. What is missing in realist accounts, is how modernization has deepened the interdependence of states and societies economically, socially and environmentally. This interdependence has accelerated in post-Second World War years due to the democratization and the emancipation of societies as well as technological developments at the level of information, communication and transport technology and infrastructure. In this new world, all levels of society, including companies, civil society, branches of government, etc. – and no longer ‘the statespersons’ representing the state as an aggregate – participate to this interdependence. The latter involves new transnational connections and networks that transcend states. In this modern world, security is no longer the only issue on top of the foreign policy agenda; economic stability, energy, etc. are equally and sometimes more important. Robert Keohane and Joseph Nye coined the term complex interdependence to depict the new ontological reality of the world they perceived in the 1970s (Robert O. Keohane & Nye, 1977). In later years, they defined globalization as enhanced complex interdependence (Robert O. Keohane & Nye Jr, 2000).

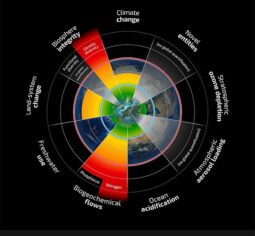

Complex interdependence modifies how states define their interests. In a world that has become so interconnected, national states’ individual fates get more and more intertwined. Part of the story of interdependence is also about intervulnerability; not only opportunities but also risks are to be addressed. In a world of financial crises, climate change, pandemics, international terrorism, water, food and energy scarcity, etc., national states – which remain as egoistic and rational as before – perceive more and more common interests. These common interests generate a demand for more international cooperation (Robert O. Keohane, 1982). Under pressure of the circumstances that follow from complex interdependence and globalization, states are even compelled to cooperate to secure their self-interest.

But what then about the problem of relative gains that was said to impede cooperation? In a world of complex interdependence, states are not only interested in security and relative power. There are so many problems to be managed and opportunities to be grasped – with regard to trade, environmental protection, police cooperation, etc. –, with little bearing on a states’ international security position, that very often absolute gains matter the most.

Still, there are the issues of free riding and cheating that according to realists work as strong disincentives to cooperation, as exemplified by the prisoner’s dilemma. Neoliberal institutionalists counter this argument by pointing out that in a complex, transnationalizing society, there are numerous occasions to cooperate on a daily basis. These are mostly not unique and existential matters, as the prisoner’s dilemma suggests. In contrast, plenty of recurring opportunities for cooperation present themselves that leave room for experiment; if another free rides or cheats, that does not mean the end of the world. Moreover, free riders and cheaters are discouraged, because they also have an interest in cooperation and therefore need to uphold a good reputation, not to get excluded and isolated later. This ‘shadow of the future’ also stimulates reciprocity: when you are loyal to your partners in a collaborative arrangement, your partners are likely to return it, especially at moments that are important for you (Robert O Keohane, 1984; Oye, 1985). In due course, we arrive at a much more optimistic outlook on international cooperation.

The demand for international regimes

In today’s world, issue areas (e.g. trade, monetary cooperation) acquire a high issue-density, which refers to the high number and importance of issues to be addressed. Besides common interests and basic confidence, smooth and durable cooperation requires efficiency. For that purpose, states have set up relatively stable institutions that help to overcome information and transaction costs (i.e. the costs to obtain information on the issues and on the other partners, and to negotiate about the terms of the transaction). Such arrangements are international regimes. The most cited seminal publication on international regimes is the 1982 special issue of the journal International Organization, in which issue editor Stephen Krasner defined international regimes as follows (Krasner, 1982): “An international regime is a set of implicit or explicit principles, norms, rules and decision-making procedures around which actors’ expectations converge in a given area of international relations.”

Hence, a regime can take several forms. The arrangement can be explicit (e.g. written down in a treaty) or implicit (i.e. an unwritten understanding). The regime possesses a hierarchy of rules, from general principles (e.g. the idea of free trade in the world trade regime, centered upon the World Trade Organization (WTO)), over more concrete norms (e.g. the norm of national treatment, or non-discrimination between foreign and domestic companies) to specific rules (e.g. maximum tariffs per product), apart from decision-making procedures, which also include dispute settlement arrangements. Around those rules of the game “actors’ expectations converge” – this formulation suggests that international regimes often allow flexibility and room for interpretation of the rules. In the real world, regimes are

• almost completely informal and unwritten (like the post-1815 balance of power mechanism);

• only based on a loose ‘memorandum of understanding’;

• based on a formal, legally-binding treaty;

• or on a treaty plus an intergovernmental organization with a secretariat (e.g. the WTO).

The effects of international regimes

So far, we have spoken about the demand for international cooperation and for international regimes. But international regimes also have certain effects. To start with, international regimes help to make international politics more predictable. This advantage, in its turn, makes international regimes more durable: states tend to remain loyal to the international regime as they do not want to plunge into the unknown by going back to chaos and the law of the jungle. States’ loyalty is reinforced by reputation effects and reciprocity, as already referred to above.

In addition, the more issues regimes cover, the more room is created for fruitful negotiation and widening and deepening of the regime. To secure agreement, a state can make side-payments to another to compensate for certain disadvantages. Through ‘linkage’, states can trade concessions by means of package deals within and between regimes.

Regimes also tend to proliferate as an institutional form. Success of one regime can spill-over into regime-building in other policy areas, either by generating new problems and adding pressures to cooperate in adjacent issue areas (e.g. how trade liberalization increases pressures to address international crime), or encouraged by increased trust from previous experiences.

At the end of the day, complex interdependence has bound great powers and smaller states into a dense and ever expanding web of international regimes. Neoliberal institutionalists believe that this enmeshment in international collaboration constrains the power of larger states. Supported by domestic interest groups who have a big stake in the international regimes, larger states generally prove to be loyal to these regimes, since they also have an interest in a stable and predictable international environment. For most states, cooperation through international regimes is a positive sum game, even though states from time to time need to make painful concessions on certain topics for the sake of absolute net gains. The benefits states gain from institutional enmeshment and accompanying processes of socialization, eventually lead them to redefine certain interests.

Bibliography

Topics

Theories