Synopsis

Climate change has emerged as one of the most pressing global challenges of our time, and its impact extends far beyond environmental concerns. The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) defines the political dimension of climate change as "a change of climate which is attributed directly or indirectly to human activity that alters the composition of the global atmosphere and which is in addition to natural climate variability observed over comparable time periods." The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) defines climate change as "a change in the state of the climate that can be identified (e.g., by using statistical tests) by changes in the mean and/or the variability of its properties, and that persists for an extended period, typically decades or longer." Environmentalists and scientists stress the urgency of addressing climate change due to its adverse effects on ecosystems, biodiversity, and natural resources. Rising temperatures, sea-level rise, and extreme weather events are some of the observable environmental impacts. The scientific consensus, as articulated by the IPCC, states that climate change is primarily driven by human activities. The environmental perspective highlights the need for international cooperation to preserve ecosystems and prevent irreversible damage to the planet.

Climate change has become intricately entwined with international politics, affecting various aspects of diplomacy, security, development, and economic policies. At its core, climate change is a global problem that requires international cooperation. Climate change negotiations, such as the Kyoto Protocol and the Paris Agreement, represent political efforts to mitigate and adapt to climate change. These agreements demonstrate how nations collaborate to combat climate change and allocate responsibilities. The political perspective also highlights the tension between developed and developing countries regarding emissions reductions and climate finance.

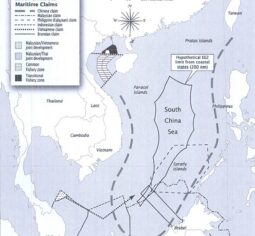

Furthermore, climate change intersects with national security concerns, adding another dimension to international politics. The destabilising effects of climate change, such as extreme weather events, sea-level rise, and resource scarcity, can exacerbate conflicts and create new security threats. The Center for Climate and Security defines climate change as "a threat multiplier...that has the potential to exacerbate existing vulnerabilities and contribute to conflict." Rising temperatures can lead to resource scarcity, including water and arable land, which may spark conflicts over these essential resources. Competition for limited resources, including water and arable land, can heighten tensions between states and trigger migration patterns, leading to political and social unrest. The security dimension of climate change highlights the need for preemptive measures and international cooperation to prevent conflicts stemming from climate-related factors.

Climate change has profound economic implications, which are a crucial aspect of its role in international relations. The shift away from fossil fuels towards renewable energy sources requires significant investments in infrastructure, research, and development. As such, climate change policies often intersect with trade negotiations and economic cooperation. Countries with advanced clean technology industries may gain a competitive advantage, while fossil fuel-dependent economies may face challenges in transitioning. Disparities in economic capacities and responsibilities contribute to debates over burden-sharing and the allocation of financial resources for climate mitigation and adaptation efforts. The economic perspective on climate involves analysing the costs, benefits, and trade-offs associated with climate action. Economists often use the concept of externalities to explain the economic dimension of climate change. Stern argues that climate change is "the greatest market failure the world has ever seen" because it results from the failure of markets to account for the costs of greenhouse gas emissions.

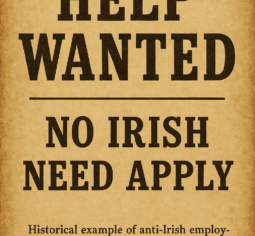

Furthermore, climate finance and the allocation of resources for mitigation and adaptation are central economic issues. Climate change has implications for global development. The impact of climate change disproportionately affects countries in the Global South that are more vulnerable to its effects due to limited adaptive capacity and socioeconomic challenges. International assistance and cooperation are crucial for supporting adaptation measures and building resilience in these countries. The climate change discourse is intertwined with debates on global justice, equity, and development assistance, with wealthier nations being expected to contribute more to address the consequences of climate change.

Developing countries demand financial support from developed nations to address climate change, emphasising the economic disparities in climate action. The economic perspective underscores the need for innovative financing mechanisms and policies to incentivize sustainable development. Climate change raises questions of justice, responsibility, and intergenerational equity. It underscores the need to consider the interests of future generations. This perspective also delves into the concept of climate justice, which seeks to address the disproportionate impacts of climate change on vulnerable populations. The ethical dimension underscores the responsibility of affluent nations to take significant steps in reducing emissions and supporting climate adaptation in developing countries.

Bibliography

Topics

Theories

About Course

Over 92% of computers are infected with Adware and spyware. Such software is rarely accompanied by uninstall utility and even when it is it almost always leaves broken Windows Registry keys behind it.

Even if you have an anti-spyware tool your Windows Registry might be broken – developers of those tools are focused on removing Adware and spyware functionality, not every trace of software itself.

Another category of software that is known to leave bits and pieces behind on uninstallation is games. There are a lot of special installation systems that creates strange files, unique entries in your registry file as well as changes system dll’s to other versions.

Creating vector illustrations

It sometimes seems everyone on the planet is using Windows. Many say Windows is way better.

Creating vector illustrations

It sometimes seems everyone on the planet is using Windows. Many say Windows is way better.

What to learn?

Work comfortably with Microsoft Excel Format spreadsheets in a professional way Be much faster carrying out regular tasks Create professional charts in Microsoft Excel Work with large amounts of data without difficulty Understand Accounting and Bookkeeping principlesInstructor