Synopsis

In today’s world, issue areas (e.g. climate, trade, monetary cooperation) exhibit a high issue-density, which refers to the high number of issues and transactions to be addressed. Besides common interests and basic confidence, smooth and durable cooperation requires efficiency. For that purpose, states have set up relatively stable institutions that help to overcome information and transaction costs. The latter refer to the costs to obtain information on the issues and on the other partners, and the costs to negotiate on the terms of each transaction. These arrangements are international regimes.

In his 1982 seminal article, Krasner defines international regimes as follows: “Regimes can be defined as sets of implicit or explicit principles, norms, rules, and decision-making procedures around which actors' expectations converge in a given area of international relations. Principles are beliefs of fact, causation, and rectitude. Norms are standards of behavior defined in terms of rights and obligations. Rules are specific prescriptions or proscriptions for action. Decision-making procedures are prevailing practices for making and implementing collective choice” (Krasner, 1982).

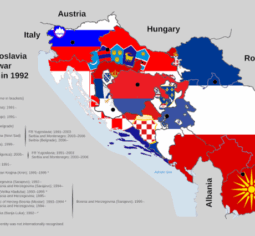

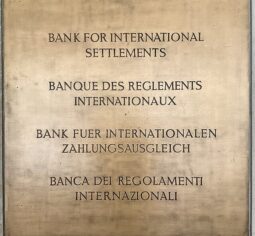

As such, international regimes are a kind of international institutions. Examples are the non-proliferation regime, centred upon the Non-Proliferation Treaty and monitored by the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA); the global trading regime centred upon the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade and related treaties, overseen by the World Trade Organization (WTO); or the unwritten Balance of Power regime implicitly agreed upon by the European great powers in the wake of the defeat of Napoleon and the 1815 Congress of Vienna.

International regime theory is concerned with why states created regime, as well as with the effects of regimes.

Work on international regimes took off in the beginning of the 1980s. Much of this work subscribed to neoliberal institutionalism. As such, it shared some basic assumptions with structural or neorealism (notably, an anarchical international system populated by rational, egoistic states), but was more optimistic about the durability of common interests in a context of complex interdependence. From this perspective, international regimes are formed to pursue those common interests. Once in place, international regimes advance states’ loyalty to the international regime and further cooperation, thanks to monitoring mechanisms, reciprocity, and reputation effects (if a state cheats in one regime, it can be punished in another) (Keohane, 1984).

Yet, international regimes have not only been studied from the interest-based neoliberal institutionalist perspective. Realist-inspired hegemonic stability theory, for example, offers a power-based theory of regimes, claiming that successful and durable regimes require the resources and/or coercion by a hegemonic power to ensure the loyalty of the weaker states. Furthermore, constructivists provide a knowledge-based theory, emphasizing the intersubjective meanings that stabilize international regimes. For an excellent overview of international regime theory and ongoing discussions, see (Hasenclever, Mayer, & Rittberger, 1997).

Bibliography

Topics

Theories