Synopsis

Hedging refers to an important phenomenon in present-day international politics. It is a variant of alignment policy that fundamentally differs from balancing and band-wagoning. In the literature hedging often refers to smaller states navigating between two or more competing great powers without choosing one side. The relationship then “[features] a mix of cooperative and confrontational elements” (Ciorciari & Haacke, 2019).

Evelyn Goh defines hedging as “a set of strategies aimed at avoiding (or planning for contingencies in) a situation in which states cannot decide upon more straightforward alternatives such as balancing, bandwagoning, or neutrality. Instead they cultivate a middle position that forestalls or avoids having to choose one side at the obvious expense of another” (Goh, 2005).

Lim and Cooper offer a similar definition, and add the notion of generating ambiguity and creating uncertainty: “Secondary states hedge by sending signals which generate ambiguity over the extent of their shared security interests with great powers, in effect eschewing clear-cut alignment with any great power, and in turn creating greater uncertainty regarding which side the secondary state would take in the event of a great power conflict” (Lim & Cooper, 2015).

In a more recent definition, Kuik includes the notion of insurance. By the way, hedging is a common notion in financial markets and refers to offsetting risks. By the same token, some states actively hedge against potential risks in their relationships with great powers. Hence, he defines hedging in international politics as “insurance-seeking behavior under situations of high uncertainty and high stakes, where a rational state avoids taking sides and pursues opposite measures vis-à-vis competing powers to have a fallback position.” This behaviour has three attributes: “(a) an insistence on not taking sides or being locked into a rigid alignment; (b) attempts to pursue opposite or contradicting measures to offset multiple risks across domains (security, political, and economic); and (c) an inclination to diversify and cultivate a fallback position” (Kuik, 2021).

In practice, in addition to offsetting risks, hedging behaviour can also be combined with seeking opportunities from selective engagement with great powers. Anyway, the idea of coping with fear in relation to relevant great powers, is an essential element of the definition of hedging. These capitals worry about a great power doing harm in whatever way, and/or about a great power withdrawing its benefits or protection.

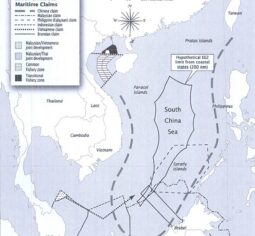

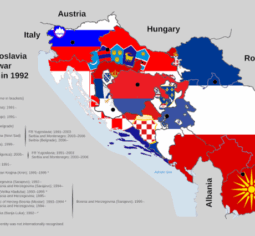

Hedging as a phenomenon gained traction after the Cold War (Ciorciari & Haacke, 2019). During the Cold War many states tightly aligned with either the US or Soviet Union to balance against the other bloc. Most of them were under very strong pressure or even forced to do so. With end of the Cold War and its bipolar straightjacket many smaller states took the freedom to obtain strategic autonomy and widen their diplomatic horizons. In recent decades, however, geopolitical shifts and increased great-power rivalry brought with them more uncertainty and risks. For example, some states in South-East Asia – so far the main focus of hedging studies – worry about the rise of China, while US protection is not certain (anymore). Hence, states such as Singapore, Philippines and Vietnam are seen hedging vis-à-vis both great powers, and more precisely engaging with both in the economic, political and security spheres (see e.g. He & Feng, 2023).

Hedging behaviour is also on the rise in the Middle East. Traditional US allies such as Turkey, Saudi Arabia, Egypt, United Arab Emirates and Israel – to varying degrees and for various reasons – are widening their options and deepening their political, economic and in some cases even military ties with Russia and China. The same can be seen in several parts of Africa, where capitals play off European ex-colonizers and donors, the US, China and Russia against each other.

Research on hedging potentially addresses many interesting questions. These can relate to forms, degrees and motivations (Kuik, 2021). Smith, for example, describes several forms of hedging (Smith, 2020). As to motivations, hedging can be approached from a neoclassical realist perspective that combines explanations derived from dynamics in the international system and from domestic politics (see e.g. He & Feng, 2023).

Bibliography

Topics

Theories