Synopsis

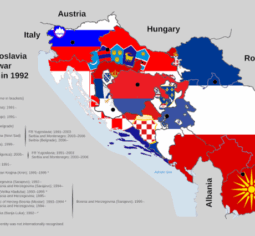

It might be helpful to start by defining the concept of intractable conflict before we address the role of emotions in the former—the term protracted conflict is also used in the literature. Coleman defines intractable conflict as: ‘[…] conflicts [that] persist for long periods of time and resist every attempt to resolve them constructively, they can appear to take on a life of their own. We label them as intractable conflicts. They can occur between individuals (as in prolonged marital disputes) and within or between groups (as evidenced in the antiabortion-prochoice conflict) or nations (as seen in the tragic events in Northern Ireland, Cyprus, and the former Yugoslavia) [a current example is the conflict between Israel and Palestine]. Over time, they tend to attract the involvement of many parties, become increasingly complicated, and give rise to a threat to basic human needs or values. Typically, they result in negative outcomes for the parties involved, ranging from mutual alienation and contempt to atrocities such as murder, rape, and genocide’ (Deutsch et al, 2006). Bar-Tal adds that ‘[t]hey are demanding, stressful, painful, exhausting, and costly both in human and material terms’ (Bar-Tal, 2000). Other scholarly luminaries have also defined intractable conflict under further labels, ‘[…]deeply rooted conflict’ (Burton, 1987), ‘protracted social conflict’ (Azar, 1990), ‘moral conflict’ (Pearce and Littlejohn, 1997) and ‘enduring rivalries’ (Goertz and Diehl, 1993).

On the role of emotions in intractable conflicts, Lindner suggest that emotions affect intractable conflicts, or they dynamics in diverse manners. For example, ‘[f]ear can lead to an avoidance of conflict (“flight”), or to a counterphobic aggressive response (“fight”), or to a desire to avoid disaster by reaching an agreement. It can hamper constructive conflict resolution or enhance it when it sharpens our senses and alerts our thoughts. [While humiliation] involves putting down, holding down, and rendering the other helpless to resist the debasement. The feeling of being humiliated emerges when one is unable to resist the debasement and one deems it to be illegitimate as well as unwanted. […]. [F]eelings of humiliation may acquire the quality and strength of obsessions and addiction. They can dominate people’s lives to the extent that their actions become destructive for themselves and others. If instigated by humiliation-entrepreneurs, such as in Rwanda in 1994, feelings of humiliation can fuel mayhem in ways that make even the purchase of expensive weaponry superfluous. In Rwanda, everybody had machetes at home for agricultural use. When people are intent to perpetrate atrocities—and feelings of humiliation may be most instrumental—costly military weaponry may not be needed for people to proceed in perpetrating mayhem’ (Deutsch et al, 2006).

Bar-Tal, Halperin and Pliskin argue that emotions (fear, hatred, and anger) contribute to the intractability of conflicts by strengthening social beliefs shared by members of a group. For example, they argue that the prolonged experience of fear can lead to ‘[…] observed cognitive effects that intensify freezing [inability to resolve the conflict]. It sensitizes the organism and the cognitive system to certain threatening cues. It prioritizes information about potential threats and causes extension of the associative networks of information about threat. It causes overestimation of danger and threat’ (Bar-Tal et all, 2015).

Bar-Tal also argues that ‘[t]he more intensive and durable the conflict, the more relevant it becomes to society members. As the conflict becomes more relevant, people become involved with it cognitively by forming various beliefs that explain the conflict situation and functionally help them to cope with it […]. The most extensive cognitive activity—which involves the formation of a conflictive ethos—takes place during intractable conflicts, which are the most extreme in severity and longevity’ (Bar-Tal 2000).

How conflicts are transmitted is a very complex web of actions and inactions, where emotions play a part and contribute to their intractability. Halperin et argues that ‘[…] the societal beliefs of the culture of conflict are strongly related to negative emotions such as, widely shared by society members. Once these emotions are established and maintained as lasting emotional sentiments, they activate thoughts in line with the societal beliefs of the ethos’ (Halperin et al. 2011b). ‘A typical example of a negative emotion that often has an obstructing effect on peacemaking processes is the chronic fear that is often an inherent part of the psychological repertoire of society members involved in intractable conflict. In many cases, fear in this violent context may even lead to the development of collective angst, which indicates a perception of the group’s possible extinction’ (Wohl and Branscombe 2008 ; Wohl et al. 2010 ).

A luminary on conflict resolution, John Paul Lederach, addresses steps to resolve intractable conflict. He states that ‘[p]eacebuilding is an enormously complex endeavor in unbelievably complex, dynamic, […] I had often thought about and suggested that a peacebuilder must embrace complexity, not ignore or run from it’ (Lederach 2005). Lederach continues, ‘[t]ime and again, where in small or large ways the shackles of violence are broken, we find a singular tap root that gives life to the moral imagination: the capacity of individuals and communities to imagine themselves in a web of relationship even with their enemies. […] First and foremost, where cycles of violence are overcome, people demonstrate a capacity to envision and give birth to that which already exists, a wider set of interdependent relationships. This is akin to the aesthetic and artistic process. […] The artistic process has this dialectic nature: It arises from human experience and then shapes, gives expression and meaning to, that experience. […] Literally, people in settings of violence experience and see the web of patterns and connections in which they are embroiled. […] Breaking violence requires that people embrace a more fundamental truth: Who we have been, are, and will be emerges and shapes itself in a context of relational interdependency. […] A second and equally important discipline that emerges from the centrality of relationship is found in an act of simple humility and self-recognition. […] They situate and recognize themselves as part of the pattern. Patterns of violence are never superseded without acts that have a confessional quality at their base. Spontaneous or intentionally planned, these acts emerge from a voice that says in the simplest of terms: “I am part of this pattern. My choices and behaviors affect it.” While the justification of violent response has many tributaries, the moral imagination that rises beyond violence has but two: taking personal responsibility and acknowledging relational mutuality. […] Peacebuilding requires a vision of relationship. Stated bluntly, if there is no capacity to imagine the canvas of mutual relationships and situate oneself as part of that historic and ever-evolving web, peacebuilding collapses’ (Lederach 2005).

Bibliography

Topics

Theories