Synopsis

The theory of peripheral realism was developed by the Argentine political scientist Carlos Escudé (1948–2021) from the early 1980s onward. Although it originated in the experience of Latin American countries, the theory is applicable worldwide (Schenoni & Escudé, 2016).

Peripheral realism departs from three key critiques of neorealism:

• The abstraction of the ‘state’: Neorealism’s notion of the state is analytically unhelpful because it ignores the internal complexity of states. A state encompasses not just a government but an entire society, including the political regime, social structure, political culture, and more. In this sense, peripheral realism shares affinities with neoclassical realism.

• A broader conception of the national interest: In today’s world, the national interest involves not only security but also the priority of economic development.

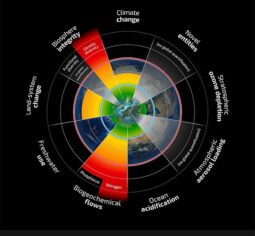

• A hierarchical international system: The international system is not truly “anarchical”; rather, it is structured as a hierarchy between more and less powerful states.

Within this hierarchy, today’s world is divided into three categories: rule-makers, rule-takers, and rebels:

• Rule-makers are essentially the great powers with nuclear weapons, plus Germany. Since the end of the Cold War, this group has been dominated by the United States.

• Rule-takers include most other countries, which accept the dominance of the rule-makers and seek to avoid confrontation. This broad category includes multiple subgroups, such as rich middle powers (e.g., Japan, Canada), powerful developing countries (e.g., India, Brazil), and poorer states further down the hierarchy.

• Rebels openly confront the rule-makers, especially the United States. Examples include Saddam Hussein’s Iraq, the Ayatollahs’ Iran, and North Korea.

A central claim of peripheral realism is that most states consider economic development more important than foreign policy autonomy. To maximize security, they tend to bandwagon with the hegemonic power – particularly the United States in the Americas – rather than prioritize autonomy and risk confrontation. The more democratic or ‘citizen-centered’ a state is, the more likely it is to bandwagon and avoid conflict with the hegemon, because this aligns with what the citizenry expects and for which it holds governments accountable. This insight resonates with democratic peace theory. Developing countries are especially vulnerable and therefore have even stronger incentives to follow this path.

By contrast, some authoritarian states – primarily concerned with the interests and prestige of ruling elites – are less attentive to the economic welfare of the broader population. Some prioritize regime power and prestige and pursue bold, costly foreign policies that maximize autonomy. This may involve confronting the United States (or other major powers), engaging in military adventures, and taking other risks, with the costs largely borne by the population. Such behavior is legitimized through nationalist propaganda and enforced through repression. As Escudé puts it, “total foreign policy autonomy = absolute domestic tyranny.”

Peripheral realism also offers policy prescriptions: in a unipolar or multipolar world, weaker states are better served by prioritizing economic development over autonomy and by bandwagoning with the major powers – as Chile and Colombia have done in recent decades in relation to the United States. Rebels, by contrast, are likely to be defeated. Latin American examples include the Argentine military junta’s reckless 1982 war against the United Kingdom over the Falklands/Malvinas, and the confrontational posture of Venezuelan presidents Chávez and Maduro toward the US-led order.

For Latin America and other regions, an important question today is how to navigate a world that has shifted from unipolarity to multipolarity. In much of the Global South, US predominance is now challenged by China and a resurgent Russia. According to Schenoni and Escudé, “moderation and prudence are therefore necessary virtues for any statesman trying to navigate the troubled waters of power transition between China and the US. A radical tack with any of these partners could damage growth, democracy, or even sovereignty.” One option for states is to seek greater autonomy by cultivating equally strong relations with the United States, China, the EU, and Russia (i.e. ‘equidistance’). But what happens if one major power – such as the United States under Trump – actively pressures states to adopt exclusive alignments?

Bibliography

Topics

Theories