Synopsis

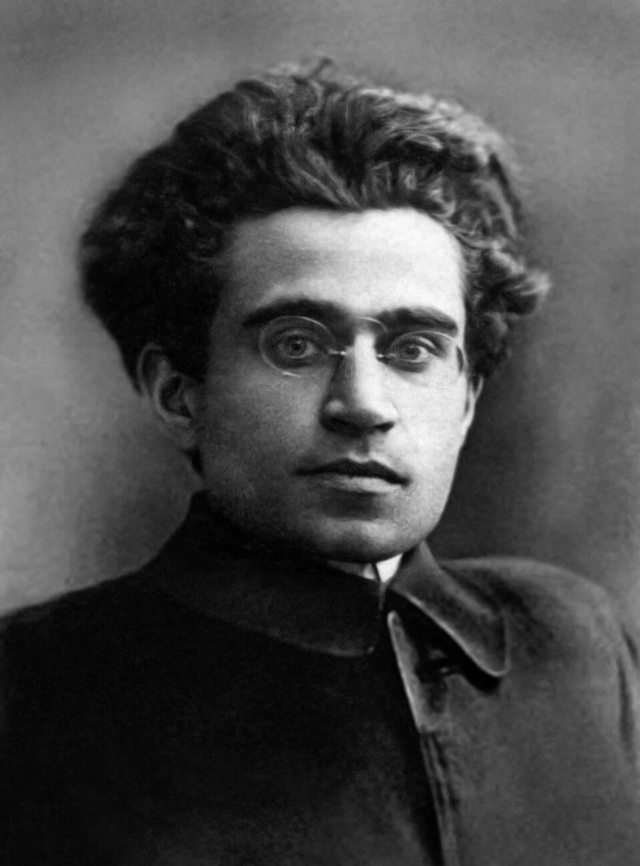

Neo-Gramscian IPE scholars like Robert Cox (York University, Canada) subscribe to ‘critical theory’ as opposed to ‘problem-solving theory.’ The latter does not question or problematise the existing order, which includes the international states system and the global capitalist system. Mainstream strands such as realism and liberalism are limited to solving scientific problems, i.e. explaining international phenomena (e.g. conflict, balance of power, cooperation) within the existing order. Critical theory, in contrast, does not take the existing order for granted, but regards it as an explanandum (something to be explained). Furthermore, critical theorists also reject the ideas of the neutral scientist and power- and value-neutral theory. As Cox famously put it: “Theory is always for someone and for some purpose” (Cox, 1981). Theories are always selective and distortive lenses to understand the international reality, and always both emphasise and neglect important aspects and dimensions. Realism, for example, assumes the primacy of states and their ‘national security interest’ over the interests of human beings and our planet’s ecosystem. Liberalism tends to overlook the implications of capitalism, class struggle and exploitation, hence missing essential dimensions of world politics. Finally critical theorists are explicit about being driven by the search for justice and emancipatory change.

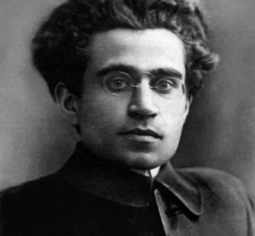

Robert Cox applied Gramsci’s theory for domestic societies to the international realm. Cox equally recognises the interplay of material capabilities, institutions and ideas within societies and within world politics. The material capabilities include the means and modes of production (land/nature, labor and capital, including technology). Institutions are broadly defined in the sociological sense, i.e. encompassing not only formal political institutions such as parliaments and intergovernmental organisations, but also laws, decision-making procedures and the unwritten, informal institutionalised practices that regulate society. Ideas are also largely defined, including ethical values, ideology, scientific convictions, etc. These three elements constantly interact. A certain configuration of these three elements is referred to as a historical structure.

Such three-legged historical structures operate at the three levels of social activity Cox distinguishes: 1) social relations of production; 2) forms of state; and 3) world order. The social relations of production “[encompass] the totality of social relations in material, institutional and discursive forms that engender particular social forces” (Bieler & Morton, 2004, p. 4). This level corresponds with the Gramscian notion of ‘civil society.’ This society includes the economy. It is where actors and groups interact with each other, and where the interplay of material capabilities, ideas and institutions (see below) shapes social forces (or classes), their respective control over material resources, and the power relations among them. This configuration of classes, class interests and power relations determines the form of the state. The latter corresponds with the ‘political society.’ In other words, Gramsci and the neo-Gramscians will always define the state in relation to its societal base, offering a wider theory of the state than realists. Therefore, they prefer to consider the ‘integral state’ or ‘state-society complex’, rather than merely focusing on the state apparatus in the narrow sense. It is the state-society complex – thus including the power relations between classes with their respective interests – that largely determines a country’s foreign policy. Finally, world order refers to the level of international economy and politics, which rests on the social relations of production and forms of state of greater and smaller powers.

How is hegemony articulated throughout the historical structure at three levels of social activity? Within the social relations of production of a certain country, a certain alliance of classes, which controls the main means and modes of production, can become hegemonic, in the sense that the subordinate classes largely embrace its ideology as their own. Ideas and institutions operate to bolster and stabilise the hegemony and the interests of the ruling social forces – which is a typically Gramscian observation. Consequently, the form of state is actually led by the ruling alliance and shaped in line with its interests. If that state happens to be the leading great power in the international system – i.e. with the most economic and military resources – the leading alliance can project its hegemony onto other countries. This consolidation of hegemony at the level of world order occurs in collaboration with national social forces with similar interests and their governments. The hegemonic state will actively work to foster and empower similar and likeminded social forces in subordinate countries. There, the hegemonic power is then viewed as benevolent, and its global leadership legitimate. According to Cox, these countries together then constitute the scene of an international historical bloc, characterised by hegemony (Cox, 1981, 1987).

Bibliography

Theories