Synopsis

The democratic peace theory is associated with two propositions:

1) Democracies almost never wage war against each other.

2) Democracies are inherently more peaceful.

The democratic peace theory is quite influential in the West and has informed foreign policy of the US and other countries. Governments and commentators believe that the world will become a more peaceful place as democracy spreads. Therefore we should oppose and rollback dictatorships. For example, in his 1994 State of the Union, US President Bill Clinton stated the following (Clinton, 1994; Mansfield & Snyder, 1995):

'Ultimately, the best strategy to ensure our security and to build a durable peace is to support the advance of democracy elsewhere. Democracies don’t attack each other, they make better trading partners and partners in diplomacy. That is why we have supported, you and I, the democratic reformers in Russia and in the other states of the former Soviet bloc. I applaud the bipartisan support this Congress provided last year for our initiatives to help Russia, Ukraine, and the other states through their epic transformations.'

The idea that democracy causes peace was already present in Kant’s Perpetual Peace. To test related claims, democratic peace theorists have conducted large statistical studies. They drew from big databases such as University of Michigan’s Correlates of War project (for wars) and the Polity Project (for regimes) (Hayes, 2012; Hegre, 2014; Ray, 1998). In this research, regime types as independent variables are neatly operationalized to distinguish democracies from non-democracies. To go beyond this binary and simplistic operationalization, several studies also consider the quality of democracy and put regimes on a more nuanced continuum. As to dependent variables, the focus is on inter-state wars, i.e. wars between states with a minimum death rate, leaving out intra-state wars and armed clashes with lower numbers of casualties.

There exists robust evidence that confirms the first, or dyadic, claim: democracies almost never fight wars with each other. According to Jack Levy “this absence of war between democracies comes as close as anything we have to an empirical law in international relations” (Levy, 1988). Thomas Risse-Kappen confirms: “There is no other empirical finding in the realm of international relations that has reached a similar consensus among scholars” (Risse-Kappen, 1995). However, there is no evidence for the monadic claim that democracies are less war-prone than non-democracies.

Monadic explanations

Establishing a correlation between variables is one thing. Another is showing a causal mechanism and explain it. Perhaps the best known explanation was already provided by Kant himself, and is in fact monadic: in a ‘republic’ with a constitution, representative government and separation of powers, ultimate political power rests with the citizens, and they are the ones who would suffer the most from war, since they are the ones who die on the battlefield as soldiers, are hit by the enemy’s attacks, and suffer social-economic hardship. Hence, a democratic government will think twice before going to war, not to be voted out at the next election. In a dictatorship, the government has much more possibilities to ignore and oppress dissenting voices. However, even authoritarian regimes are to some degree constrained by the risk of revolution or a ‘palace’ coup.

In a similar vein, another monadic explanation focuses on institutional constraints. In a democracy, power is shared between institutions, which keep each other in check, and in a few cases – depending on the constitution – work as veto players. Here we think of the leader and executive branch sharing power with, or even being subordinate to, parliament with regard to foreign policy and the decision to go to war – and perhaps some power for the courts in case of ‘illegal’ decisions. Additionally, the press, civil society and public opinion can play a role in reigning in a bellicose government.

Some scholars also contend that democratic governments need to take into account higher ‘audience costs’: if they go to war, they cannot afford to lose, since democracy will punish them. Therefore, they refrain from going to war, and if they fight, they will mobilize sufficient resources to make sure they will win. This selectivity is making democracies more peaceful. This propensity to ‘choose their wars’ also has a preventive effect: by signaling resolve, democracies are less likely targets of aggression, and hence less involved in war.

These monadic explanations certainly help to explain why democracies not always recur to war during tensions with others. But since democracies are not significantly more peaceful than non-democracies, the mechanisms highlighted by these explanations need to be offset against other factors, which apparently prevail in the many instances when democracies actually go to war.

Dyadic explanations

Dyadic explanations focus on interaction between countries and explain why democracies almost never go to war with each other. In their domestic setting, democracies by definition tend to apply non-violent ways to settle disputes among social groups, based on strong legitimate institutions and the rule of law. They externalize or project this attitude to their foreign affairs, especially when they deal with other democracies, which operate in the same way. Thus, on questions such as land and maritime borders, management of rivers, etc., peaceful solutions can be worked out.

Democracies are also more transparent – with regard to military strategy, capabilities, maneuvers – which reduces distrust and miscalculations on the part of others. In addition, thanks to the free press and the free opposition, leaders have more difficulties to demonize other states based on false information. In other words, democracy reduces the security dilemma (Risse-Kappen, 1995). This transparency works best for peace among democracies. Less transparent dictatorships can more easily demonize and be demonized or misunderstood.

Finally, a constructivist account for the dyadic peace has been put forward. At the level of identity, democracies have come to see themselves as part of an in-group as friends, and tend to other the non-democracies as adversaries. This common identity – which corresponds with security communities (see below) – is believed to strongly reduce the likelihood of war among democracies (Risse-Kappen, 1995).

Critique

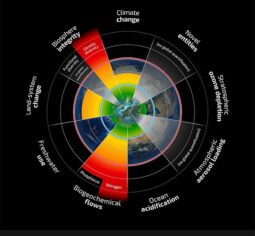

It is not easy to criticize the dyadic claim given the robust empirical evidence. However, some scholars question the direction of the causation. Does democracy cause peace, or is it peace that makes democracy flourish? Peace is conducive to trade, investment and economic growth, which reduce societal tensions and frustrations, and then fosters democracy. Furthermore, in a peaceful international or regional environment, governments feel less need to recur to authoritarianism and repression; peace is making it somewhat easier for a country to be democratic. Peace itself, then, could have been caused by other factors than democracy. Maybe peace among democracies and democracy both stem from another cause, notably economic welfare. From a Marxist perspective we could theorize about how the so unequal spread of welfare has come about, so that it is mostly the rich countries that can enjoy the alleged ‘democratic peace’. All this does not preclude democracy, in its turn, from reinforcing peace.

Other kinds of criticism rather target a) the narrow scope of the democratic peace theory for everything it omits, and b) the widely advertised claim in public discourse that democracies are inherently peaceful despite the weak evidence.

As to the narrow scope, most contributions of the democratic peace theory only consider inter-state wars with a minimum number of casualties (often a threshold of 1,000 is taken) as dependent variables. This omits ‘smaller skirmishes’; civil wars; wars within colonial empires; wars between US colonists and native peoples (Ravlo et al., 2003); non-armed ways of harming other countries, such as supporting coup d’états, supporting armed proxies, economic sanctions, cyber war. In addition, democratic peace theory is not concerned about and uncritical about how the democratic zone of peace came about; exploitative capitalism and imperialism might have generated the wealth that helps the ‘free world’ to remain peaceful, depriving that economic welfare to others, leaving those to poor, highly unequal and unstable societies, oppressed by authoritarian regimes.

Many arguments have been put forward to explain why democracies are not inherently peaceful and often initiate wars. Mansfield and Snyder found that since 1811 many countries going through the transition from dictatorship to democracy were aggressive, including versus other democracies. Very young democracies without deeply rooted democratic values and without strong values easily fall prey to populist, ultranationalist, demagogic governments that mobilize the masses for war, for example for irredentist agendas, i.e. attempts to ‘regain lost’ territory (Mansfield & Snyder, 1995). As we have seen in recent years, any democracy can bring ultranationalist leaders to power, who erode democratic values and institutions, and can turn out to be warmongers. Still, due his isolationist ‘America First’ platform and widely shared war fatigue in the US, president Donald Trump refrained from large military operations, unlike several of his predecessors.

The idea that in democracies press, civil society and public opinion keep hawkish governments in check, must be qualified (Rosato, 2003). In the past two centuries, these actors have sometimes been more bellicose that their government. Sometimes the press in democratic countries lacks to be sufficiently critical. Despite high numbers in several cases, civilian casualties in the countries where Western armies fight – euphemistically referred to as ‘collateral damage’ – seldom receive intense and sustained attention in prime-time TV programs or popular newspapers, and only rarely bring governments into political trouble at home. Furthermore, ultranationalist movements and the military-industrial complex can exert influence over governments and press for military adventures.

In their Democratic Wars, Geis et al. examined the mechanisms under which liberal democracies initiate wars (Geis et al., 2006). To maintain or expand their colonial empires or spheres of influence democracies have very often attacked other countries. This happened in the era of ‘high imperialism’ (1880-1914), during the Cold War, and beyond. Many operations have been motivated as an effort to neutralize weapons of mass destruction (e.g. falsely for 2003 US and UK invasion of Iraq), as ‘humanitarian interventions’ (e.g. the NATO operations in Yugoslavia in 1999 and Libya in 2011), or as efforts to fight crime (e.g. the US invasion in Panama in 1989). These interventions are often partly or fully driven by a genuine ‘liberal messianism’, the believe that authoritarian regimes should not exist because they violate human rights and make the world unsafe and that the ‘free world’ should do something about that. The observation that this drives much unilateral aggression from democracies does not constitute a moral judgement per se, but it should not be ignored and can of course be problematized from various angles.

The threshold for democracies to go to war has significantly been lowered through technological developments that undo Kant’s argument that in a democratic country the citizens who have the most power tend to oppose war because they are also the ones who will suffer the most. With high-tech air force, sophisticated missiles and drones, wars can now be fought in ways that minimize the risks for the own military personnel and population. In recent years, in many Western countries, citizens have not felt like their country is ‘at war’, even though their armies operated in places such as Afghanistan, Iraq, Libya, or Syria.

Bibliography

Topics

Theories