Synopsis

‘Status’ and ‘prestige’ can be treated as synonyms, alongside definitions mentioned below. In some uses, the only difference is that status can also signify an element of rank, a relative position in a hierarchy. This notion is only relevant in a relational context. Furthermore, it is always an ideational element. Actors can confer upon each other status or prestige, and may have an idea of their own and others’ status or prestige (Mercer, 2017).

For Paul, Larson and Wohlforth status can be compounded as ‘collective beliefs about a given state’s ranking in valued attributes (wealth, coercive capabilities, culture, demographic position, sociopolitical organization, and diplomatic clout)’ (Paul et al, 2014).

Renshon posits that in international relations status relates to a state’s rank in a community: ‘[it] combine[s] to make any actor’s status position a function of the higher-order, collective beliefs of a given community of actors. […] “Status community” is defined as a hierarchy composed of the group of actors that a state perceives itself as being in competition with. […]. Since status is based on higher-order beliefs, there is no objective, time-invariant formula for what qualities or attributes confer status. […s]tatus is as an identity or membership in a group, such as “status as a major power’ (Renshon 2017). This is somehow is mirrored by Kassab: ‘Status has more to do with identification and cannot be measured objectively, but only through studying narratives and the perceptions of those narratives by the subject and others.’ (Kassab 2024).

Status-inconsistency, then, “occurs either when major power status attribution is not in sync with the capabilities and/or foreign policy pursuits of the state in question” (Volgy et al., 2011, p. 7). However, if a state has the capabilities needed to project power it can expect, potentially, to obtain higher status if it pursuits violence. Renshon argues that ‘[…] states can expect to profit from higher status, and because status is positional (and thus other states can be expected to be reluctant to cede status voluntarily), violence and conflict may be one way of achieving higher status rather than a last resort after having failed to do so’ (Renshon 2017).

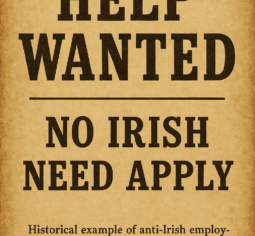

Barnhart links status in relation to previous humiliations asserting that ‘[h]umiliated states engage in [hegemonic behaviours] because these acts define high international status and because participating in them enables those who identify with the state to overcome humiliation and to thereby regain a sense of collective efficacy and authority. Furthermore, the acts promise to bolster the image of the state in the eyes of others because they demonstrate the state’s distinctive capabilities as well as its intention to restore prior status’ (Barnhart 2020).

He and Feng concentrate their efforts in defining ‘role status’ vs. ‘trait status’. Role status refers to the relational and ideational conception, which we also endorse, in contrast with trait status, which refers to objective material elements. ‘While trait status refers to valued attributes that determine a state’s standing and rank in a social hierarchy, role status is constituted through state interactions and competent practices that bring the state respect and deference from others. […] For example, although North Korea has nuclear weapons, it does not have the status of ‘great power’ because other states do not collectively perceive or recognize it as such. In this sense, North Korea’s ‘great power’ status is not socially accepted and recognized, despite its possession of nuclear weapons’ (He & Feng 2022).

For Gilpin prestige works as an ‘[…]everyday currency of international politics, […] where the weaker states lean to recognise the legitimacy of the current international order, allowing for the hegemon to achieve its interest without the use of force (Gilpin 1981).

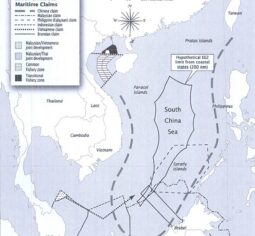

‘An established power’s prestige plays a critical role in enabling it to govern the international order and controversies over the hierarchy of prestige in the system—namely, when it lags behind changes in the distribution of power—are an important source of international political change The recent rise within China of nationalistic demands for power and prestige suggests that economic growth alone may not lead to a satisfied rising China or correspond to the role it envisions for itself’ (Murray 2019).

Kassab approaches the meaning of prestige within a historical framework: ‘[…] the more powerful a state becomes, the more it seeks to overturn past humiliation through aggressive prestige-seeking acts. This is done to reassert its power and status to achieve this prestige even at the expense of others. […] Similarly, status quo states seek to protect their prestige at the humiliation of revisionist or subdued powers’ […]Part of state behavior is the need or desire of states to defend or increase status’ (Kassab 2024).

Bibliography

Topics