Synopsis

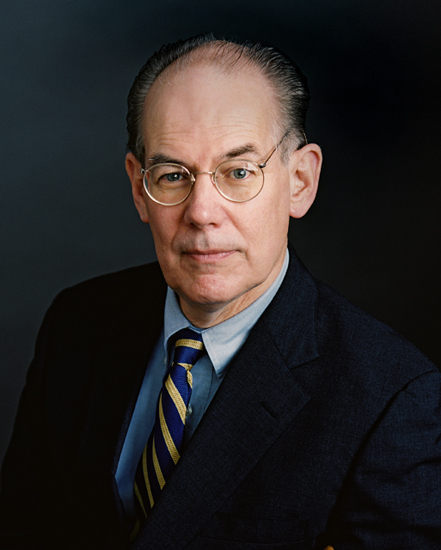

Offensive realism is a branch of structural realism, also known as neorealism. The theory was developed and named by U.S. scholar John Mearsheimer (2014).

According to Mearsheimer, all great powers strive to maximize their share of global power. They will persist in this pursuit until they achieve global hegemony, as this position offers the only true guarantee of security. For Mearsheimer, “[a] hegemon is a state that is so powerful that it dominates all the other states in the system. No other state has the military wherewithal to put a serious fight against it” (2014: 40).

Mearsheimer’s theory follows from five bedrock assumptions on international politics:

1. The international system is anarchic. It consists of independent states with no central authority above them. This anarchy creates what is called the "911 problem": there is no global authority to which a threatened state can call for help.

2. Every great power possesses some offensive military capability, enabling it to inflict serious harm on, even destroy, others. As a result, all great powers pose a potential threat to each other.

3. States can never be certain about the intentions of other states.

4. Survival is the primary goal of great powers. This includes preserving their territorial integrity and domestic political order. Without survival, no other objectives – such as ideological aims – can be meaningfully pursued.

5. Great powers are rational actors. They are aware of their external environment, understand both their own and others’ preferences, and take into account how their actions will influence the behavior of others. They consider both the short- and long-term consequences of their decisions.

From these assumptions result three general patterns of behavior: fear, self-help and power maximization. In the anarchical international system, great powers can never trust each other. Relying on self-help to survive, they are never sure to have amassed enough power to withstand any attack from others. The result is a relentless quest for maximal power.

In their interactions, great powers adopt a zero-sum mentality: any gain by one is perceived as a loss by another, and vice versa. Consequently, each great power seeks to shift the balance of power in its favor – through economic, diplomatic, or military means – whenever a viable opportunity arises at an acceptable cost. At the same time, they will attempt to block similar efforts by rival powers.

Due to the anarchic nature of the international system and its consequences, great powers are, by definition, revisionist and offensive. This is the only way to survive. As long as no global hegemon exists – a scenario Mearsheimer considers unlikely – there will be enduring great power competition and the constant risk of war. This persistent struggle is the essence of The Tragedy of Great Power Politics, the title of Mearsheimer’s seminal book first published in 2001.

Achieving global hegemony is nearly impossible for any single great power. A major obstacle lies in the difficulty of projecting power across oceans—these "stopping waters" not only offer protection but also hinder the ability to dominate the globe.

However, great powers can become regional hegemons. Even then, they remain vigilant, wary of potential challengers. For this reason, a regional hegemon does not want to see a great power in another region rise to hegemonic status, as it could pose a future military threat.

As long as other powers within a region are capable of blocking such a bid for dominance, the existing regional hegemon will typically stay on the sidelines. But when those local powers are no longer able to contain the aspiring hegemon, the regional hegemon is likely to intervene.

The US is the only regional hegemon in the world. During WWI, WWII and the Cold War it sent its troops to fight in Europe and Asia to stave off German or Soviet regional hegemony.

As a neorealist, Mearsheimer adheres to a parsimonious theoretical approach, treating states as black boxes or billiard balls – abstracting away from individuals and domestic political dynamics. He acknowledges, however, that offensive realism does not explain everything. The rare exceptions often involve factors that neorealism intentionally excludes.

In this way, offensive realism functions as both an explanatory and a prescriptive theory. While most great powers tend to behave in line with its predictions – given the limited strategic options available – there remains the possibility of "foolish" policies that deviate from the rational course. These must be warned against. This explains why Mearsheimer frequently offers policy advice to the United States, particularly regarding its relations with China and Russia.

Mearsheimer has attracted many critics. One of them, classical realist Jonathan Kirshner, argues that Mearsheimer’s thinking is overly mechanistic and deterministic – especially in the context of US-China relations. Mearsheimer sees war between the two as nearly inevitable and advises the United States to do everything possible to contain China’s rise (Mearsheimer, 2021).

Kirshner, by contrast, questions whether China even aspires to global hegemony. He suggests that China may have learned from the catastrophic failures of past would-be hegemons like Napoleon and Hitler. Rather than pursuing dominance, China may expect others to accommodate its rise through diplomacy and compromise. In line with classical realism, Kirshner emphasizes that statespersons typically have a range of options. Deterministic policy advice, he warns, can be not only misguided but potentially dangerous (Kirshner, 2012).

Bibliography

Topics

Theories