Synopsis

Climate Justice Now, a global network of organisations and movements working towards fighting for social, ecological and gender justice also support this vision. “From the perspective of climate justice, it is imperative that responsibility for reducing emissions and financing systemic transformation is taken by those who have benefited most from the past 250 years of economic development. Furthermore, any solutions to climate change must protect the most vulnerable, compensate those who are displaced, guarantee individual and collective rights, and respect peoples’ right to participate in decisions that impact on their lives (Climate Justice Now 2008).

The environmental movement, also known as the climate justice movement, is not merely a movement for the preservation of the environment but goes beyond to demand for social, economic and gender justice. The inception of the environmental justice movement has its roots in the convergence of all these issues. Schlosberg and Collins write: “Many academics and activists trace the beginning of the environmental justice movement to the 1982 protests of the disposal of PCB-tainted soil at a new landfill in Warren County, North Carolina. The resistance to dumping highly toxic waste in a poor, majority African-American community brought together civil rights activists and black political leaders, along with environmentalists, and was the first major action joining civil rights and white campaigners since the 1960s. Some saw the event as the beginning of a ‘merger of the environmental and civil rights movements’, and publicization of the unlikely coalition helped to spur the development of a national movement” (Schlosberg and Collins 2014).

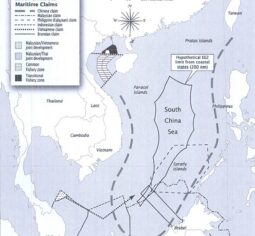

The climate justice movement employs a range of tactics to achieve its goals. “First and foremost, climate justice campaigners continue to highlight the disproportionate impacts of climate disruptions on the lives and livelihoods of the most vulnerable and politically marginalized populations, from indigenous nations and peasant communities in the South to impoverished urban centres in the global North. The leadership, priorities, and strategic insights of front-line activists are at the centre of effective climate justice organizing and lend a far greater urgency to climate action in all its diverse forms. Second, climate justice advocates bring an understanding that the institutions and economic policies responsible for climate destabilization are also underlying causes of poverty and economic inequality. For many activists, the built-in growth imperative and increasing concentrations of wealth that are central to modern capitalism are at the roots of both social and environmental problems, and a transition to a more inclusive and democratic economic system is necessary to meaningfully address the climate crisis. Climate justice advocates also remain highly sceptical of efforts to implement climate policies through market mechanisms such as the trading of pollution permits and the creation of carbon offsets, citing the substantive inadequacies of existing carbon trading programs, as well as the long-range consequences of further commodifying the atmosphere […].”

“Third, climate justice brings a broadly intersectional outlook into the climate movement. The concept of ‘intersectionality’ was first proposed by the feminist legal scholar Kimberle Crenshaw […], in an effort to ‘conceptualize the way the law responded to issues where both race and gender discrimination were involved,’ and has been embraced by climate justice activists as a means to address the many common threads that link environmental abuses to patterns of discrimination by race, class, gender, sexual orientation, and other social factors. This awareness is further reinforced by organizational and interpersonal practices aimed at challenging manifestations of oppression and social hierarchy both within the climate movement and in society at large” (Jafry 2019).

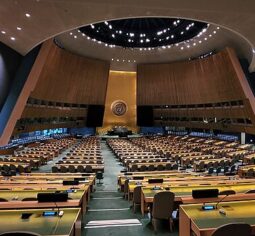

A very central aspect of the climate justice movement is that the solutions to global injustices will not come from a top-bottom approach but through a systemic shift that must come from below and also address capitalism. For Dawson, “Genuine solutions to the climate crisis cannot emerge from climate negotiations, whether on a domestic or international level, unless significant pressure – pressure that outweighs that of powerful corporate interests – is brought to bear by a globally linked, locally grounded group of social movements mobilizing around the theme of climate justice. This will take genuine organizing – a task that the Left in general and cultural studies in particular has been prone to shy away from. organizing is a particularly urgent task on both a practical and a theoretical level given the predominantly anarchist, anti-statist character of the global justice movement in the North. Rather than abdicating engagement with the organs of state power, the crisis of our times requires transformation of these organs through practices of radical democracy. In addition, however, a movement for climate justice needs a theoretical grasp of the economic, political, and ecological stakes at play in the new Green Capitalist order” (Dawson 2010).

Dawson critiques the notion of Green Capitalism as anything but another cycle of capital accumulation. She states that this system “….does not seek to and will not solve the underlying ecological contradictions of capital’s insatiable appetite for ceaselessly expanding accumulation on a finite environmental base. Instead, Green Capitalism seeks to profit from the current crisis. In doing so, it remorselessly intensifies the contradictions, the natural destruction and human suffering, associated with ecocide” (Dawson 2010).

Bibliography

Topics

Theories